Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SIR ISAAC BROCK - SHIP THAT NEVER SAILED

History is the truthful reconstruction of the past.

"He that commands the sea is at great liberty and may take as much and as little of the war as he will." Francis Bacon

At the start of the War of 1812, Major-General Isaac Brock said that the fate of Canada rested ultimately on Britain's "retaining naval control of Lakes Ontario and Erie." Whoever controlled the waterways controlled the outcome of the war.Domination of the Great Lakes was essential to maintaining communication with and support for any military forces in the region, for the waterways served in place of roads for the movement of troops and supplies.

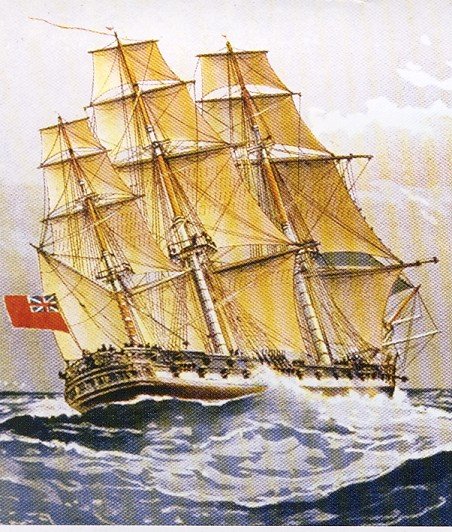

The Americans realized this too and both countries scrambled to add firepower to their fleets with massive construction progammes with gunboats, schooners, brigs and ships sliding down their slipways. The ships-of-the-line, wooden-walled, sail driven and armed with smooth bore cannon were to appear in great number on the lakes. In a sense this naval war was a shipbuilder's war because the shipbuilder provided the tools which the sailors used to fight the war. Canadian and American shipyards engaged in a naval armaments race in which some of the largest battleships then afloat were built.

|

|

Control The Waterways |

|

|

Ships of War on the Great Lakes |

Nowhere did the marriage of cannon and sail see such astonishing results as occurred in the early 18 hundreds on the shores of Lake Ontario. Shipbuilding efforts at Kingston and Sackets Harbour progressed rapidly from sloops to frigates and finally culminated with the commissioning of legendary HMS St. Lawrence. At the end of the war, she had sister ships on the stocks at Kingston and there were two American rivals in the same state at Sackets Harbour. At Kingston the British launched the ten-gun brig the Duke of Gloucester. The Americans at Sackets Harbour fired back with the eighteen-gun brig Oneida. The British laid the keel at Kingston of the 22-gun corvette Royal George and the pattern and pace of the "ship-building war" became clearly established with each nation building ever bigger ships, believing, perhaps, as the king of Sweden once said, building small ships was only a waste of young trees.

The St. Lawrence constructed at Kingston in 1814 at the fantastic cost to the British taxpayers of $500,000 would translate in today's money as twenty million dollars. She absorbed the total resources of the Kingston dockyard for months. All the ship's gear and guns came from England. Launched on Sept. 10, 1814 the First Rate had a gun deck of 59.13 metres, an extreme breadth of 16.2 m. and a draught of 6.1 m. [See Below *] Five weeks were required to outfit the great ship before her complement of more than 1000 officers and men finally sailed on October 15th for the head of the lake - present-day Hamilton harbour. That great ship must have been a sight to behold, a thing of malevolent beauty.

The ship was designed and built by William Bell. Although it was the largest lake vessel every built for use on the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence did not have the dimensions of its salt-water cousins because it did not have to carry drinking water and months of provisions. Bell built the St. Lawrence with very few knees, a piece of timber cut with an angle like that of a knee to connect beams and used to fasten or strengthen the connection. The fact that it had none of these knees appears to have caused some of its labourers to predict the ship would break its back upon launch. No such catastrophe occurred and after his first voyage up and down the lake in his new flagship, Commodore Yeo declared, "The Saint Lawrence has completely gained Naval ascendancy on the Lake and I am happy to say she sails very superior to anything on it. " This great vessel with her escort of smaller ships called at the port of Toronto on numerous occasions.

|

|

St. Lawrence |

|

|

Naval Gun |

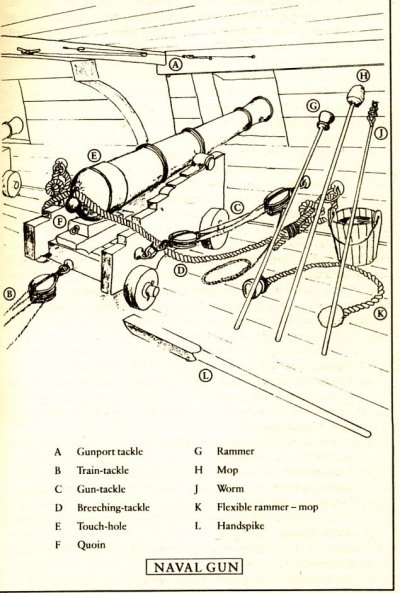

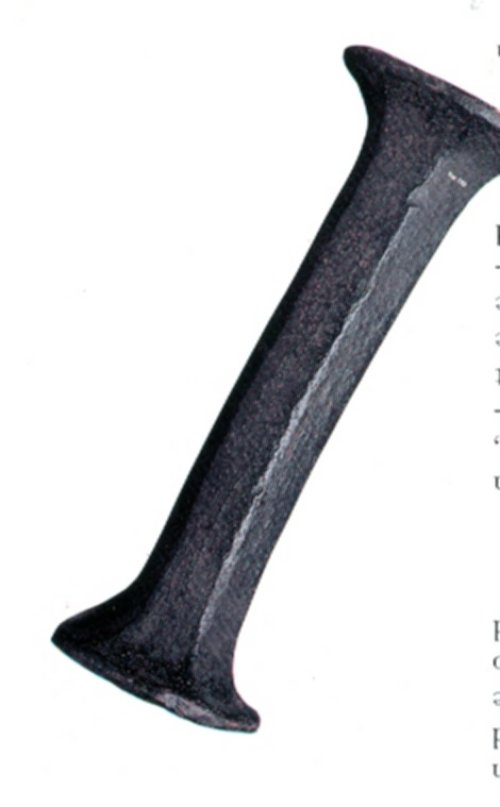

Naval Gun

1. A gunport-tackle held open the gunport.2. A train-tackle held the gun back, clear of the ship's side while it was being loaded.

3. A rammer was used to ram down the barrel, in succession: the cartridge, the ball and the wad.

4. A section of quill filled with gunpowder was inserted into the touch-hole to carry the firing spark to the cartridge.

5. A handspike was used to heave round the back of the carriage to adjust the gun's direction of fire.

6. The quoin was a wedge to be pushed under the breech end of the barrel to adjust the elevation.

7 and 8 were gun-tackles, one on each side, with which to haul the gun into its firing position after loading.

9. A flintlock firing mechanism operated by a cord enabling the gun captian to keep out of the way of the recoil while firing the gun.

10. A slow match kept glowing for use should the flintlock fail.

11.A breech tackle, a heavy roppe threaded through a rings on the breech and fastened to the ship's side on either side of the gun to limit its recoil.

12. A sponge to mop on a long handle to damp out any glowing particles left in the barrel before loading.

13. A worm like a large corkscrew on a long handle used for extracting the wad and the cartridge should it become necessary to unload the gun.

All craftsmanship in construction of the ship and all skills of the crew had one purpose: to bring into action the reason for the ship's existence their guns - cast iron barrels mounted on heavy timber carriages firing solid, cast iron shot. Three standard sizes were described by the weight of the shot: 32lb., 18lb. and 9lb. On ships of the line 32-pounders were located on the lowest gundeck; 18-pounders on the upper gundeck and 9-pounders on the quarterdeck. These latter were later replaced with 12-pounders. The upper gun deck was unobstructed from end to end except for the masts and a pair of capstans used for raising the anchor. Twenty-six 18-pounders, thirteen to each side were mounted on this deck.These cannons were long-range guns that permitted the captain to remain out of reach of the enemy while blasting away at his vessels. The number of guns each ship carried determined its rate of which there were six. The first rate had 100 guns and the sixth rate 18 guns. Most ships of the line carried 74 guns and were at least 53 metres long with two or three full gun decks.

Ships also contained carronades, short, large-bore guns which fired heavy shot a short distance. The number carried varied and did not influence the ship's rating no matter how many there were. An effective way of focussing fire was to build it into the ships vertically and so permit a three-decker ship of the line to batter its smaller opponents and survive to fight again. First and 2nd rate ships (3-deckers) were expensive to build and man because they required immense amounts of stores like food, cordage and canvas.

The St. Lawrence, a three-decker weighing 2305 tons, could launch a broadside with its 3-tiers of 112 smoothbore cannon - for the most part 32-pounders - firing solid round cannonball. The cannonade of a 3-decker in action must have been a sight and a sound to behold. Roughly speaking the St. Lawrence's broadside was equal to two of the two largest American ships together.

|

|

Nelson's Victory |

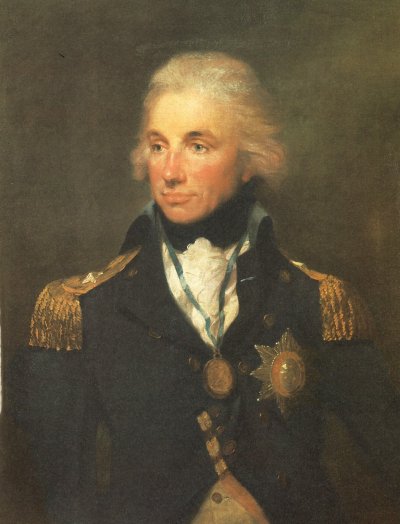

It was more powerful than Victory the flag ship of Britain's greatest naval hero Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson. Nelson was the fifth of eight children of a widowed poor parson of the Church of England. His uncle was a naval man and when he learned that Horatio wanted to go to sea, his uncle inquired, "What has poor Horace done, who is so weak that he above all the rest of the family, should be sent to rough it out at sea. But let him come and the first time we go into action, a cannon ball may knock off his head and provide for him at once." Young Nelson's name was entered on the muster book of the ship Raisonnables as of January 1, 1771. Young Horase's name was to be revered forever as one of England's greatest heroes.

|

|

Admiral Horatio Viscount Nelson |

|

|

Lord Horatio Nelson (engraving based on a portrait) |

The Victory had 100-guns: 42-pounders on the lower deck; 32-pounders on the middle deck; and 12 pounders on the upper deck.

|

|

Double-headed Shot |

A double-headed shot was for cutting through the rigging of an enemy ship. This particular example was actually fired during the Battle of Trafalgar and killed eight men aboard Admiral Nelson's ship, Victory.

Unlike th battle-scarred Victory, the St. Lawrence never fired a shot except in salute. While she never engaged the enemy, the St. Lawrence presented an impressive and very prominent threat and served to keep American warships close to port. Commodore Chauncey, the United States naval commander on the lakes, maintained a low profile in Sackets Harbour, for not even two of his largest ships could equal the fire power of the enormous new flagship of Sir James Yeo, the British commander for the lakes.

|

|

Commodore Isaac Chauncey & Sir James Lucas Yeo |

During this shipbuilders' battle as each nation alternately commissioned newer, more powerful vessels, control of the lakes seesawed back and forth between the two navies. The fleets never fought, however, and the race for command of the lakes became simply a ship-building battle of carpenters and riggers with each side constructing ever bigger ships with heavier guns and larger crews. "If either fleet was temporarily inferior, it stayed in port until it was reinforced."

Nearly all the ships were built by a workforce that at its peak reached 1200. As ship building boomed the demand for timber was massive. To construct a first rate ship of the line required 5750 oak trees, as well as numerous pine [**] and spruce to furnish masts and spars. Three huge pine masts - the main, mizzen and fore - thrust up from the deck. The main or lower mast was a massive structure, resting on the keel of the ship and rising through the decks to a height of perhaps 22 metres feet above the open deck. The mast were held in place by shrouds, heavy, tarred ropes secured tightly by lanyards and deadeyes. As many as 20 canvas sails hung from the spars (known as yards) which crossed at appropriate points on the masts. By changing the alignment of the yards and thus the angle of the sails to the wind, the ship could be made to sail in almost any direction. In addition kilometres of hemp and cordage were required.

Because wooden ships were organic - built of hundreds of pieces of natural material - they contained the seeds of their own destruction. Lake ships were constructed with green lumber and they did not weather well, the life of a vessel made of unseasoned lumber being six or seven years at best. Half of the ships constructed were lost to accident or more often decay which riddled them with rot. Unsuccessful attempts were made to accumulate stocks of seasoned timber to be used to build longer-lasting ships. Oak was the most common timber, but red cedar was considered the best wood, however, it was hard to come by in the quantity required.

British Lords of the Admiralty even tried pre-fabricating the components for warships in English yards and transporting them complete with all fittings and armaments across the ocean for assembly at Kingston. This project called "ships-in-frame" was discontinued after one such vessel, HMS Psyche was launched from Kingston on 25 December, 1814, the very same day American and British representatives in Ghent signed the peace treaty ending the War of 1812.

A ship of war was like a city, a kingdom over which ruled the captain despotically wielding his great powers benevolently or otherwise. Few men had such vast supremacy over their subodinates as the captain of a man-of-war in the age of fighting sail. He could have a man flogged senseless, make and break officers and order the ship's company into harm's way.

The powerful ship of war sailed in a line one behind the other. Their sides were immensely strong and able to take the brutal broadsides fired at them. From ahead or astern the ships were very vulnerable, a blast hitting the bow or stern could do great damage, the cannonball sometimes travelling the length of the ship inflicting death and destruction in its path. The line was an obvious formation because the bow and the stern of ships were protected by the ships ahead and aft. The line of battle was the standard fighting formation for more than two hundred years. The largest vessels were the ships of the line powerful warships suitable "to lie in the line of battle," hence the name.

Preparations for battle left little to the imagination. Hammocks were brought up on deck to provide cover from small arms. Provisions were thrown overboard including any cattle. Magazines were readied, guns pre-charged and watered-down canvas was hung as a fire curtain. High above sails were reefed and netting hung to thwart boarding parties. Rigging was reinforced with chains to help keep shot-up yards from crashing down on those below. Decks were soaked to inhibit fire and coated with sand for traction and to absorb the blood. Sides and decks were often painted red to lessen the shock of the sight of blood which was always liberally scattered around when the ship was in action. The crews were not fooled. As they ate their last cold meal - all stoves were extinguished - they knew how bloody it would be.

Ships of the line used frigates, the greyhounds of the sea, as escorts. The frigate - a third-rate vessel with single gun-decks - was the most glamorous type of ship in the navy. It was a lightly built ship that was long and low, designed for short-range, high-speed operations against weakly defended targets. It concentrated on broadside gunnery with little expectation of hand to hand fighting. It was big enough to carry significant gun power, and fast enough to evade larger enemies. Generally it was from 35 to 40 metres long with a displacement of 750 to 1000 tonnes and between 40 and 60 guns. It was likely to be given an independent role, while ships of the line normally operated in fleets off the major enemy naval bases. The frigate often fought single-ship actions against enemy frigates and reports of these were anxiously awaited by the press and public. These speedy vessels were the forerunners of modern cruisers. They were square-rigged war vessels, intermediate between a corvette and a ship of the line. The frigate was designed with an unarmed lower deck so that its guns were well above the waterline. This meant it could heel considerably and carry sail in a strong wind and heavy seas. It also meant that it could use its guns in heavy weather, while a two-decker would be unable to open its lower ports. It was much cheaper than a ship of the line. In 1789 a 38-gun frigate cost 20,830 British pounds and a 74-gun ship of the line cost 43,820 pounds.

1. frigate small, lightly built ships, long and low designed for short-range, high-speed operations against weakly defended targets. Concentrated on broadside gunnery with little expectation of hand to hand fighting |

|

British Frigate |

The frigate was used for convoy escort, commerce raiding and patrols. It also provided the main reconnaissance force for the battle fleet. A frigate could maintain its speed in lighter winds and make a slightly better course to windward. It could keep its gunports open longer than a two-decker and operate with a smaller crew. For these reasons the frigate was the best general-purpose ship of the war. Serving as the backbone of the navy and the eyes of fleet, frigates ranged ahead of the squadron to extend its vision over the horizon. Esteemed as excellent cruisers, frigates became ships built for speed and because they were fast and more manoeurvrable, they became the standard vessel of the British navy during the Napoleonic Wars. In the hazardous world of wooden warships, frigates were the dashing cohorts of the great ships of the line. For those seamen who sought action, adventure and fame in the age of sail, frigates were the ships of choice.

|

|

I Spy A Frigate |

The frigate was likely to be given an independent role while ships of the line normally operated in fleets off the major enemy naval bases. It often fought single-ship actions against enemy frigates and their confrontations were followed avidly by the press and public. Successful frigate captains achieved great fame and some became extremely rich on prize money. The frigate was designed with an unarmed lower deck so that its guns were well above the waterline. This meant it could be allowed to heel quite considerably and carry sail in a strong wind and heavy sea. It also meant that it could use its guns in heavy weather when a two-decker would be unable to open its lower ports. It was much cheaper than a ship of the line (in 1789, a 38-gun frigate cost 20,830 British pounds; a 74-gun ship of the line cost 43,820 pounds) so more could be built for a given sum. The frigate was used for convoy escort, commerce raiding, and patrols. It also provided the main reconnaissance force for the battle fleet.

A frigate was expected to take on an enemy frigate, even one of superior gun power such as the larger French and American frigates. It was not expected to take on a ship of the line because the difference in gun power was far too great - a 38 had half the broadside weight of a 64 and two-fifths of that of a 74 - and the hull scantlings were much weaker. By convention ships of the line in a fleet battle did not open fire on enemy frigates unless provoked. In other circumstances a frigate would use its superior sailing to escape.

In ideal conditions there was not much difference between the speed of a 74 and that of a frigate. Both types are recorded as 14 knots on occasion. However such speeds were rare among ships of the line. They could only be achieved by well-designed and well-trimmed ships with daring captains in ideal conditions of wind and sea. A frigate could maintain its speed in lighter winds and make a slightly better course to windward.It could keep its gunports open longer than a two-decker and operate with a smaller crew. For these reasons the frigate was the best general-purpose ship of the war.

One such frigate was to have a starring role in the armaments' race but never left the stocks. In the words of William Wordsworth she never felt, "the thrill of life along her keel." To counter the 28-gun corvette, President Madison, the British laid down a 30-gun frigate at York. It had been decided before adze was put to timber that the new frigate would honour the late, lamented Hero of Upper Canada, Sir Isaac Brock. The building of Sir Isaac Brock impacted the town of York in two ways. It gave a great number of people employment and it enticed the Americans to attack York in April, 1813.

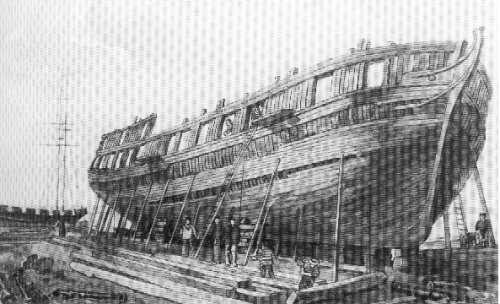

At the end of 1812, the British learned that the Americans were building warships at Sackett's Harbor, New York, and laid down two sloops of war in response. Construction of HMS Sir Isaac Brock began at York. The new ship was a sister ship to HMS Wolfe, a frigate being built at KingstonKingston, Ontario. It had a registered weight of 637 tons, and was rated as having 24 guns. In fact, the rating system often omitted carronade and Sir Isaac Brock would have had 30 guns or even more in service. (The Wolfe was completed with a medley of whatever guns were available).Although construction on both ships began around the same time, as the end of April, 1813 approached, the Wolfe was very nearly ready to be launched, while the Sir Isaac Brock was still many weeks away from being complete. It was partially planked on its starboard side and not even close to that far along on its port side. Most of the responsibility for the delay in readiness could be laid on the shoulders of shipyard Superintendent Thomas Plucknett.

The keel of Sir Isaac Brock was laid in the winter of 1813. It was expected the vessel would be finished for the opening of navigation in the spring of the same year. Construction was supervised by Thomas James Plunknett who came from Quebec to become the Storekeeper and Superintendent of the Marine Department at York. Most of those who met him questioned his ability and his mismanagement coupled with disagreement over the ship's construction site resulted in "stagnation to every exertion in the progress of the work." After a bad beginning work finally went forward on the waterfront slightly west of Bay Street.

|

|

The Sir Isaac Brock - This modern interpretation of the York dockyard shows the Brock in the final stages of its external planking. |

The ship, 40 metres long with a beam of 11 metres, was to have a complement of some 200 officers and seamen. At a time when most British navy vessels were manned by violence and maintained by cruelty, crews actually volunteered to serve on lake vessels. The crew for Sir Isaac Brock made their way across country from Halifax to York through snow-covered fields and forests. Sir Isaac was to be the second largest ship afloat on Lake Ontario, and together with the rest of the fleet at winter anchorage in Kingston, it would give Britain naval supremacy on Lake Ontario.

Spies at York kept the American military fully informed about the frigate's size, armament and construction progress. Its anticipated completion date helped influence the American decision to attack York rather than Kingston. The objective was to take or destroy the armed vessels located at York and in the process gain complete command of Lake Ontario.

|

|

I spy |

Early Monday evening of April 26th, 1813 sentries on the Scarborough Bluffs scanning the lake for any sign of enemy vessels sighted the American invasion fleet. It comprised fourteen ships under the command of Commodore Isaac Chauncey aboard the flagship President Madison. To warn the town and its garrison, a signal gun thundered out its alarm across farm and field the booming blast accompanied by a pealing church bell summoning the militiamen to York. At eight the next morning, blue-and-grey clad American riflemen wadded ashore and staggered up the steep bank to secure the high ground. Within two hours the invaders had established a beachhead just west of York and shortly thereafter had hauled down the British flag and replaced it with the Stars and Stripes.

Residents of York had watched with pride the progress being made as Sir Isaac Brock had taken shape on the skyline just west of Bay Street. With over four hundred men working feverishly to complete construction of the frigate and to complete repairs on the Duke of Gloucester, it was expected Sir Isaac would be "rigged and ready to go down the ways" in 12 weeks. However, the ship's completion was delayed by disagreements between the shipbuilder and government officials and by a shortage of supplies.

After some short, ineffective skirmishes with the Americans attackers the commanding officer, Major-General Roger Hale Sheaffe, decided to make a strategic withdrawal to Kingston leaving the citizens of York "standing in the street like a parcel of sheep." Before departing Sheaffe ordered the destruction of everything of value including Chauncey's primary target: Sir Isaac Brock, which the Americans had singled out for seizure or destruction. Sheaffe had anticipated this and warned Lord Bathurst, Secretary of War and the Colonies, that because the ship was so large, it "would be an object of no small importance to the enemy." Despite this fore knowledge of American intentions, little was done to protect the valuable new vessel.

Sheaffe directed a squad of York militiamen to torch the frigate on the stocks. As citizens looked on in dismay, roaring flames quickly converted 'their' graceful ship into a smoldering ruin. For days afterwards the air round about was pungent with the stench of burning pine, pitch and tar.

|

|

Torched! |

Outraged at being out-manoeuvred and loosing this valuable loot the Americans charged that Sir Isaac Brock had been incinerated during surrender negotiations, an act that would have violated the terms of capitulation which required all public stores, naval and military, to be yielded up to the victors. A subsequent investigation determined that the ship had, in fact, been destroyed before surrender talks began.

The Americans did take the 10-gun brig Duke of Gloucester as well as a great quantity of naval equipment and stores intended for shipment to Niagara and to Fort Malden for use there on the ship Detroit, then under construction at Amherstburg. As listed by Chauncey this booty included, "twenty cannon of different calibres from 32 to 6 pounders, a number of muskets, large quantities of ammunition, shot, shells and munitions."

Dearborn's men also took 2500 pounds from the provincial treasury. Carried away also was York's fine fire engine and most of the books from York's little library, some of which were later returned by a very embarrassed Commodore Chauncey. The American ships were so overloaded with booty that for want of space they dumped large quantities of pork and flour into the lake.

On September 10th on Lake Erie, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry defeated one-armed Captain Robert Barclay, whose defeat was due partly to the loss of the above-mentioned naval equipment at York. The American victory on Lake Erie cost Britain control of the upper lakes but she maintained mastery of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence to the end of the war.

When the greatest British commander of that age, the Duke of Wellington, was offered command in America he replied, "not a general, nor general officers, nor troops" were needed. What was required was superiority on the lakes. "I shall do you little good in America and I shall go there only to sign a peace which might as well be signed now." Shortly thereafter peace prevailed. When news of the Treaty of Ghent, that was signed on December 24th, 1814, reached Lake Ontario, all work on incomplete ships was suspended and these skeletons remained on the stocks for years, monuments to the recognition by British and Americans alike of the enormous importance of the naval command of Lake Ontario . Most of the American ships were sold or broken up soon after 1821. Their English counterparts remained on the lists a little longer, but they too were sold between 1832 and 1837.

[*] A draught of no more than 2.6 metres was necessary for most ships when loaded in order for them to pass over the sand bars that obstructed most of the rivers and creeks feeding into Lake Ontario otherwise they could not carry out activities close to shore. [**] Masts for the British navy were furnished from the nearby primeval forest, some of whose great pines were 33 metres long and a metre feet in diameter. Ship building boomed and the consumption of timber was prodigious. To construct a first rate ship of the line required 5750 oak trees, as well as numerous pine and spruce to furnish masts and spars. In addition kilometres of hemp and cordage were required. [The History of Ship by Richard Woodman, 1997]Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator